The Unexpected Diagnosis

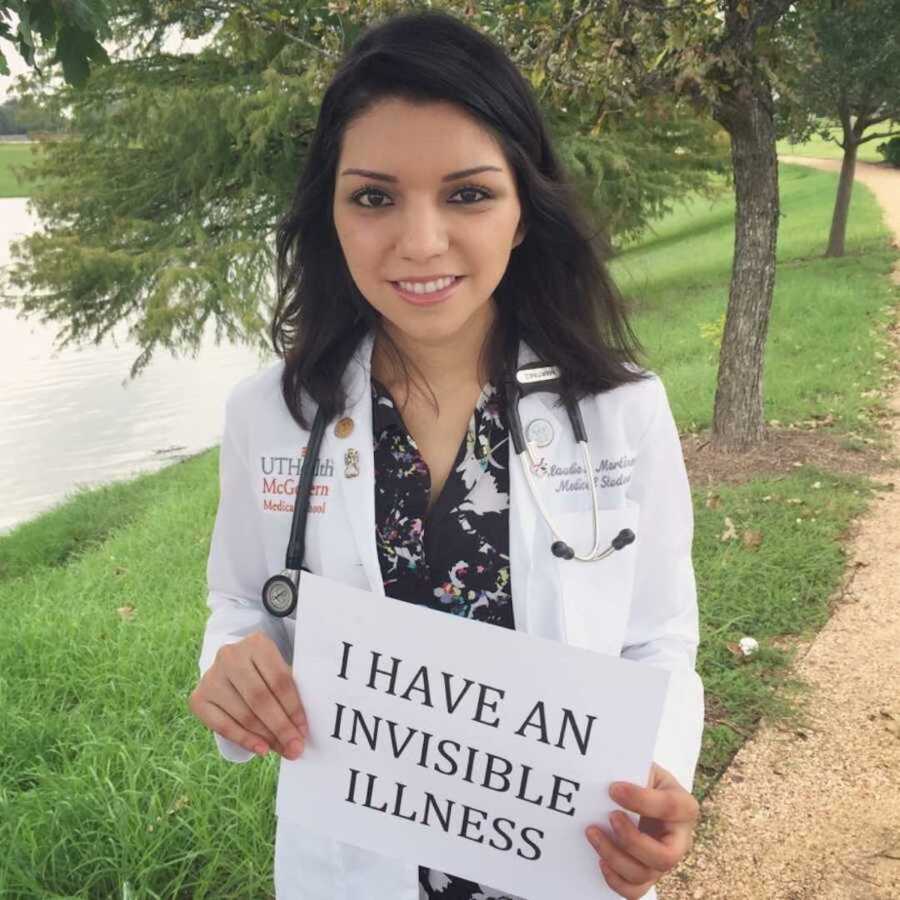

“Never in my life did I think I would be living off a feeding tube that goes into my stomach and small intestine nor did I think I would be living off a port that goes into my heart for IV fluid hydration. But, somehow, this is where life has brought me. This, all this, is what is keeping me alive. I am not your average medical student studying to be a doctor, beneath MY white coat lives a patient.

In 2011, as an undergraduate, I was diagnosed with Chiari Malformation, a condition in which a portion of the brain, the cerebellum, herniates out of the bottom of the skull and compresses the brainstem, and Syringomyelia, the development of a fluid-filled cyst within the spinal cord.

Since then, I’ve undergone six major brain surgeries, multiple shunt surgeries, multiple feeding tubes and port surgeries, as well as countless procedures and hospitalizations.

Along the way I’ve been diagnosed with hydrocephalus (a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain), trigeminal neuralgia (a chronic pain condition that affects the fifth cranial nerve), gastroparesis (partial paralysis of the stomach) and a tethered brainstem (in which the brainstem becomes pinned to the dura, or outer covering of the brain). All while going to college and now medical school.

Undergoing Experimental Surgery

On Feb. 6, 2017 my life was forever changed. I went into the operating room as one person and came out as another. Although I’m no stranger to brain surgery, this time was different.

I underwent an experimental surgery to untether my brainstem, which had attached itself to the outer covering of my brain and was pulling some of the surrounding cranial nerves along with it.

As a result, my vision was compromised, I had lost nearly all muscle control in my pharynx and esophagus, making it extremely difficult to swallow and my body was deteriorating.

After searching the literature, I found only a handful of patients who had undergone this surgery and most of the cases didn’t end well. With all odds against me, I agreed to this risky operation.

As I awoke from surgery, the doctors and I quickly realized something was wrong. Although the surgery was successful, I had suffered a stroke to my brainstem during the operation, leaving me, initially, unable to function from the neck down. I couldn’t sit up on my own, move to turn in bed, walk, bathe or dress myself. All I could do was lay in bed.

My dream of becoming a doctor felt like it was shattering before me, once again, but I’ve never allowed my health to keep me from continuing my journey and I wasn’t going to let it start now.

Regaining My Strength Back

After a few weeks, I was transferred to TIRR Memorial Hermann to undergo intense inpatient neurorehabilitation. Each day was filled with physical, speech and occupational therapy, among other activities. Every simple thing we do and take for granted in everyday life I had to relearn. Absolutely everything.

When asked what my goal was, I always said, ‘I just want to be able to take care of patients and go back to school to become a doctor.’

I spent many months at TIRR Memorial Hermann, first working on gaining the strength to sit up unassisted and then slowly advancing to standing on my own. The REX robotic exoskeleton was one of the devices that helped teach me how to walk again. The days were hard, long and, at times, frustrating, but every sensation and movement gained was rewarding.

Never Giving Up

As a medical student, I still had tests to study for and assignments to complete. Initially, I couldn’t operate my computer, write or even turn the pages in a book.

When I could finally see clearly and listen, my mother placed ear buds in my ears and played lectures for me to watch. She typed my essays as I called out my thoughts, turned the pages in my books and wrote my notes.

We started studying early—before my doctors came in to round and the long days of therapy began—or stayed up late after exhausting days. It was extremely difficult, but I was determined.

Many people couldn’t understand why I never wanted to take a break from school. While in the hospital, I didn’t watch movies or take naps. I studied. God has always preserved my intelligence during my many brain surgeries and I wasn’t going to waste that precious gift.

My brain, at times my greatest challenge, was my biggest ally in continuing my path to becoming a doctor.

Over the past seven years, doctor’s offices and waiting rooms have become my school. I’ve always wanted to become a doctor, but I never thought I’d be working towards a medical degree while being a patient, as well.

When Hard Work Pays Off

I always hoped for the day I’d be cured, when I’d no longer be the patient, only the doctor, because for so long I was made to believe the two could not exist at the same time. You are one or the other—the patient or the doctor.

I am now starting my third year at McGovern Medical School. As I sit here in the hospital waiting to see the next patient, wearing a white coat and a stethoscope around my neck, I, too, look like a patient.

I carry a heavy backpack containing liters of IV fluids, nutritional feedings and a feeding tube pump, heparin and saline flushes, syringes, dressings, caps and sterile swabs. A tube from my port that goes into my heart and a GJ feeding tube that goes into my small intestine tethers me to this backpack. My gait is abnormal and my hand function is quite limited.

But as I contemplate my situation, there is a part of me that hopes I am never cured. Perhaps I am not meant to be a ‘normal’ doctor, but a voice to bridge the gap of those who are solely doctors and those who are solely patients.

Over the years, some doctors, professors and advisors told me to quit medical school. They said, ‘Your medical history is too extensive’ and ‘You don’t have the functioning you need’ and ‘It is impossible for you to continue school while being a patient in the hospital so much.’ Some said, ‘If you do continue, you need to hide the deficits and illnesses you have.’

I remember one neurologist walked into my hospital room and asked everyone to leave. She sat down at the foot of my bed and looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Claudia, you have to give it up, you can’t be a doctor.’

After telling her I disagreed, she told me, ‘Look at where they are and look at where you are.’ (‘They’ referred to my classmates who were rounding with her on my case.) ‘Lift up your legs!’ she yelled. ‘Lift up your legs!’ At the time I couldn’t move my legs. ‘See, you can’t even lift up your own legs. You can’t even take care of yourself. How can you take care of a patient?’

You may see a young woman who has overcome adversity with resilience, time and time again, but I hope you also see a woman who is only human, a woman with a disability and medical history neither she nor her doctors can change, a woman who is good enough to become a doctor, despite everything.

My journey has been long and at times has felt impossible, but I’ve learned we don’t necessarily need a cure. We need inclusion, we need patience, we need accessibility and we need individuals who are willing to work with us to give us the reasonable accommodations that, by law, we are entitled to.

Yes, I’m here to advocate for myself, but more importantly for those who do not yet have a voice, for those coming after me and for my future patients. If I can set a trail to guide others so they don’t have to suffer as much as I have then it will all be worth it.

There is so much beauty, talent and potential in individuals affected by a disability and/or a chronic illness we just have to be willing to embrace them. At the end of the day we are all human. We are only human.

A while back, advisors told me to keep quiet about my disability. To be discrete and not let others know unless they figured it out. Instead, they have given me a platform, a platform I have used to speak loudly from. Over the years I have tried to advocate and raise awareness. Despite my setbacks, I still made it a priority to found and organize the Conquer Chiari 5k Walk in Houston, Tx. After 3 years, we have raised over $55,000 for Chiari Malformation research and united families who have someone with this neurological disorder.

I have worked with organizations such as Fight Like A Warrior, an organization that unites people with chronic and/or invisible illnesses.

Giving Back

More recently I am working to create a program that, each year, will grant someone who has a disability a wish. Individuals with disabilities can often do what everyone else can, we just need the right adaptable equipment to make these activities accessible to us.

Unfortunately, many people cannot afford the equipment they need to make the activities they once loved adaptable because many of these items are fairly expensive and much of their income goes towards healthcare costs in addition to everyday living expenses.

I am hoping my program can grant wishes and provide the equipment they need to be able to hold onto a part of themselves. They may feel as though they are losing after having their life drastically changed by something like a spinal cord injury or brain injury.

Many people say I am an inspiration, someone who needs to share their story with the world. But I am just a girl who has a dream to become a doctor. A dream that far outweighs everything I’ve endured.

And to those, like myself, who find themselves on both sides of medicine or find themselves with a disability, remember this: They say there is light at the end of the tunnel, but I’ve learned there may never be a true ‘end’ to a medical condition. That the light may stay beyond our reach.

But, perhaps, this is when we should create light for ourselves, to encourage others to see us just as we are, to show how we can shine despite darkness.”

This story was submitted to Love What Matters by Claudia Martinez. You can follow her Instagram and Facebook. Join the Love What Matters family and subscribe to our newsletter.

Read more stories like this:

Provide hope for someone struggling. Share this story on Facebook with your friends and family.