School Exam Results

“This child speaks French better than anyone else in this school,’ the director says to the crowd of faces crammed into the small room as he points to my Shoeshine Boy. I concentrate all of my efforts into translating his French into English, word by word, in my head. It is a slow and painful process. For every word I understand, I miss two more.

I steal a quick glance at my Shoeshine Boy, who is sitting next to me, to see if he understood what the director said about his French. He winks at me in response, confirming he did. My husband reaches out and squeezes my hand. It is a moment of intense pride and all of our smiles match as we wait for the director to continue.

My Shoeshine Boy has been in this Haitian school for three months now and has just finished his quarterly exams – the first exams he has ever taken in his life. This meeting is mandatory for all parents in order to obtain their child’s scores. Although we do not want to be here at 3 p.m. on the Sunday before my husband will leave for a month, my Shoeshine Boy needs us to be, so we are.

I continue to beam with pride, despite the heat that is radiating all around me. The air inside the room is hot and heavy, stale with the smell of perspiration and labored breathing. I shift my weight on the hard seat beneath me, noting the drops of sweat gathering at the back of my knees where they meet the wooden bench.

Until recently, I hadn’t even known it was possible to sweat behind one’s knees. Boy oh boy, was this Caribbean island teaching me a ton of new things.

‘But he cannot read or write.’

I gasp. Did I understand him correctly? Surely, I did not. Surely, he did not just tell this entire congregation of parents that my Shoeshine Boy could not read or write.

Surely, he did not shame him when he has been trying so very very very hard to do well in school, which is no easy feat considering that until three months prior, he had never even been before!

Feeling Hopeless

Another glance at my Shoeshine Boy confirms I have not misunderstood what has been said. His beautiful radiant smile has been replaced by fat tears that pour down his face, wetting his shirt – the one he meticulously ironed so he would look his best at this meeting. With embarrassment, he covers his face with his arm and dives towards me. The classroom goes red.

The peeling yellow paint, the ancient green chalkboard, the brown scratched benches, all red. I glare daggers. If my eyes were weapons, I would have wiped this director out without even meaning to. I wrap my Shoeshine Boy up into my arms and comfort him as if he were a toddler.

‘I am proud of you,’ I say over and over and over in my broken French. ‘You have nothing to be ashamed of. You tried so hard. I am so proud of you.’

I look out at the 30 pairs of eyes that have been staring in our direction for the past 20 minutes. They all know who we are, of course. The American family who has taken in a Haitian street kid. I see their interest in this new development – the shaming director, the crying boy, the pissed off white lady.

And although I want to scream at them all to mind their own f*cking business, instead I smile, ignoring the self-conscious nag in my brain that is caused by the line of sweat across my shirt where my belly folds over when I sit. Making enemies surely won’t help my Shoeshine Boy so I continue to beam until I feel my chin start to waiver with the forced exertion of it.

‘What have I done? What have I done?’ I ask myself over and over.

Why did I take this boy from a life he knew and put him in this place? Maybe this is too much for him.

Maybe he was right the first time we met, a year ago, when he told me he was illiterate but it wasn’t a problem because he didn’t need to learn to read to shine shoes.

‘WHERE IS THE F*CKING MANUAL?’ I ask God, silently. Even Google had no answer to the question I constantly asked anyone who would listen — ‘What do you do when you love a street kid from a very poor country and you want to make his life better, but you do not know how?’

Education Journey

As his big hot tears drip down my neck to mingle with the sweat stains on my shirt, I think back to a few months ago, to the day we went from school to school to school to try and find one that would enroll him.

‘Did he go to school last year?’ the Dominican woman asked me from across a ratty old desk.

‘I don’t think so,’ I replied, aware that toddlers from Scandinavia probably spoke better Spanish than I did.

I held my head high and looked her in the eyes. ‘Please,’ I pleaded. ‘He must go to school. He must learn to read and write, or he will shine shoes on the street forever.’

‘We will not take him here, ‘ she responded with a nod that made it obvious we had been dismissed.

My Shoeshine Boy looked down at the ground, but not before I could see the tears shining in his eyes. ‘Don’t worry, buddy, we aren’t done. There are lots of other schools in this town. LOTS OF OTHER SCHOOLS IN THIS TOWN THAT WILL TAKE OUR MONEY!’ I emphasized in my best baby Spanish so the old lady on the other side of the desk could hear me.

In truth, this whole bribery thing was new to me and made me extremely uncomfortable, but I was a quick study – and in the Dominican Republic, a couple of dollars stretched a long way towards getting what you needed, be it a fresh coconut, a taxi, or an education (or so I hoped).

She turned up her nose. ‘He is Haitian, ‘ she responded. As if that explained everything.

‘I KNOW YOU CANNOT DENY A CHILD AN EDUCATION BASED UPON HIS NATIONALITY,’ I wanted to yell out, but I didn’t know those words in Spanish. Besides, I didn’t think she cared much about what the laws mandated here.

Instead, I grabbed my Shoeshine Boy’s hand, squeezed it encouragingly and walked out into the rain where my four-wheeler was waiting for us. ‘One down, lots to go,’ I said as we climbed onto the seat and headed down the road.

At the second school, we got a similar response.

And the third.

And the fourth.

The fifth school was a Haitian school. ‘We’d be happy to accept him,’ the man in the orange checkered shirt told me in French. ‘But, of course, you would need to pay his tuition and fees right up front.’

‘Of course,’ I responded, knowing full well all the other parents were not asked to do this. ‘May I just have a tour, first?’ One peek into the classroom was all I needed to know that this school was not a fit. The oldest child in the room was no older than seven.

Onto the sixth school. By this time, we had been school hunting for hours and both of our dispositions had grown bleak. ‘I think this is the one,’ I said to my Shoeshine Boy, knowing nothing about the school besides the fact it was Haitian and there were teenagers around. He was accepted immediately when I offered to pay all the school fees upfront, including a fee for a uniform and shoes he never would receive.

Studying Hard

My Shoeshine Boy started school the very next day – big-eyed and afraid. ‘Just do your best,’ my husband and I told him as we said our goodbyes at the front door.

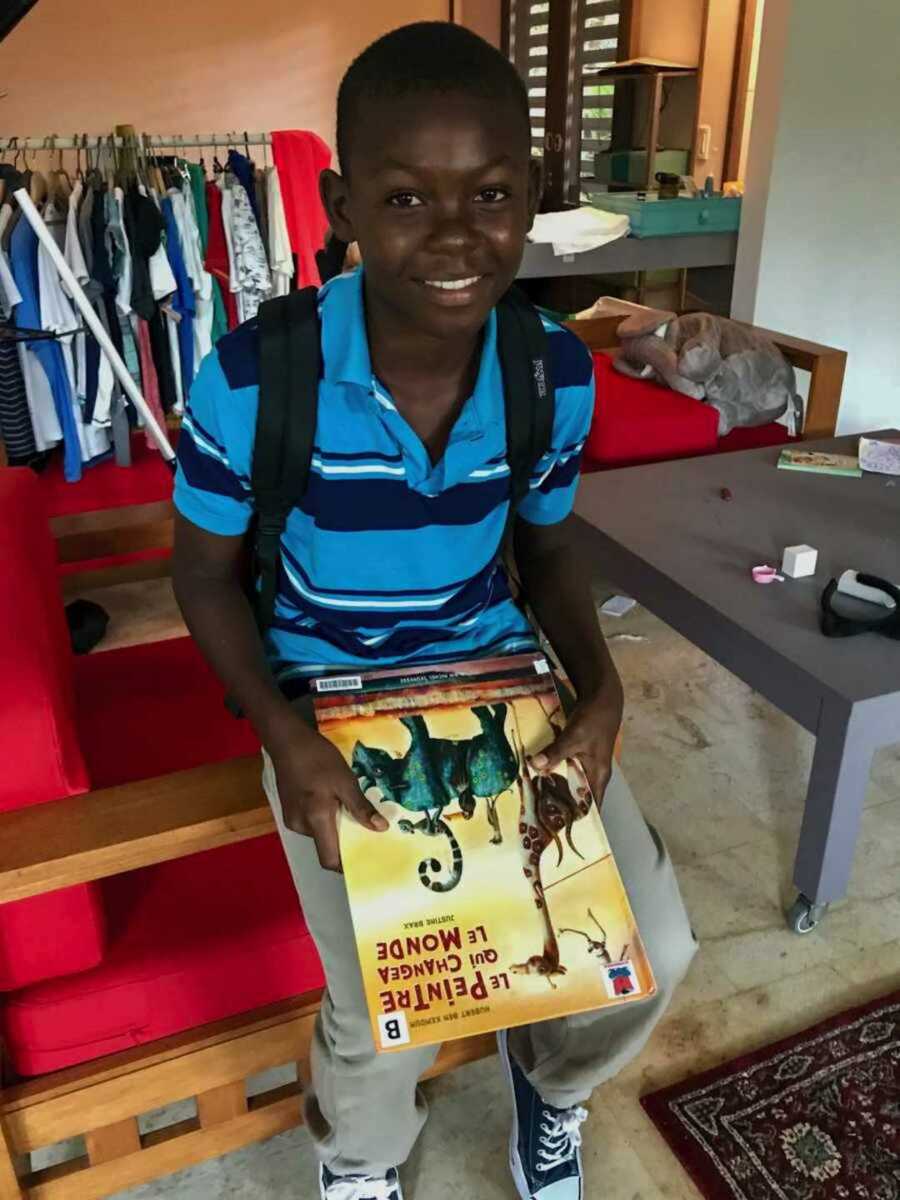

And he did. For the past few months, he had been meeting twice a week with a French tutor. Although he didn’t speak much French when he first came to live with us, his progress was astounding. He had also been disappearing for hours with his books – hiding under his bed or behind the curtains where he drilled himself over and over and over again with a combination of math sums and beginner French text.

For weeks, he had been talking about this day, asking us, multiple times, if we were going to make it, with such excitement that it brought tears to my eyes.

And now, here we were – in a room so hot I can no longer tell whether it is tears or sweat pouring down my neck where his face hides from all the people staring at us.

Back at home, My Shoeshine Boy runs to his room in tears while I sit, feeling absolutely defeated, at the dining room table. ‘It’s okay, baby,’ my husband says to me as he tucks my Shoeshine Boy’s report card into our memory drawer – I can see the equivalent of American D’s and F’s covering the surface of it. ‘His spoken French is coming along, and he will learn to read and write one day.’

Staying Determined

‘But what if we made a mistake?’ I blubber out. The tears I have held back for the past two hours come raining down.

‘What if he doesn’t want to go back? What if he hates it? What if, after all of this effort, his bubble has been burst? What if he decides to just go back to shining shoes on the street?’

‘Just give him some time,’ my husband responds and although I want to go in and wrap my Shoeshine Boy with my mother’s prayers and words of encouragement, I make myself follow my husband’s advice and give him space instead.

The night passes slowly as I throw myself into my family’s evening activities – making dinner, doing dishes and taking turns reading to my younger kids. And when my household quiets and is filled with the rise and fall of peaceful dreams, I get out of bed and creep down the stairs to pray outside of my Shoeshine Boy’s room.

I fall to my knees and pray with such intensity, quiet sobs wrack my body. I pray with everything that I am and all the love I have to give that God will protect this child and guide us in what needs to be done so we can help him as best as we can.

As I say Amen, get back to my feet and turn for the stairs, I hear a soft voice whispering from my Shoeshine Boy’s room:

‘One plus one is two, two plus two is four, three plus three is six…'”

This story was submitted to Love What Matters by Jaci Ohayon of Colorado. Follow her on Instagram. Be sure to subscribe to our free email newsletter for our best stories.

Read more stories from Jaci here:

Do you know someone who could benefit from reading this? SHARE this story on Facebook with family and friends.